Learning more about the progress of medicine throughout the centuries

(Modern Medical Technology reveals more about King Tut, Part 2 of 2)

Howard Carter, and other archeologists who discovered King Tut, are blamed for much of the damage to his bodily remains

More than thirty golden statuettes of King Tutankhamun and various deities were found in the young king's tomb, among them this gilded wooden figure of Tut as the king of Lower Egypt.

Details of the results of the CT Scan (Computed Tomography Scan)

CT Scans or electronic impulses recorded on a magnetic disk and processed by a minicomputer for reconstruction display of the body in cross-sections.

The scientists who have been working to analyze the CT scan images of Tutankhamun came together in a series of meetings on March 3 and 4, 2005, to discuss their findings. The scientists were unanimous on almost all points. Their conclusions are as follows:

- Condition of the Mummy: The remains of the pharaoh are in very poor shape, due primarily to the damage done by Carter's team. The body is in a number of pieces, with both upper and lower limbs dismantled. Many parts present at the original examination are now missing, although many fragments remain loose in the sand tray. Both bones and skin are broken in numerous places. The king's arms, originally folded across the chest, are now by his sides.

- Tut's Age at Death: Tutankhamun was about nineteen years old when he died, based on the following observations, and using modern developmental tables:

- The fusion of the epiphyseal plates (the parts of the bone that is responsible for growth until a certain age) matches the development of a young man of 18 or more, and 20 or less.

- All of the cranial sutures are still at least partly open.

- The wisdom teeth are not completely erupted. One of these (upper left) is impacted, and there is a slight thinning of the sinus cavity above. This was not life-threatening, and there are no signs of infection.

- Tut's General Health: Judging from his bones, the king was generally in good health. His internal organs, as is usual for Egyptian mummies, are not present in the body, and so they have not been analyzed. There are no signs of malnutrition or infectious disease during childhood. His teeth are in excellent condition, and he appears to have been well fed and cared for.

- Tut's Size in Life: Tutankhamun was approximately 170 cm. (5 and a half feet) tall, as extrapolated from the measurement of the tibia (lower leg). He was slightly built (gracile or gracefully slender).

- Tut's Skull Shape: Tutankhamun had a very elongated (dolichocephalic) skull. The cranial sutures are not prematurely fused, so this is most likely due to normal anthropological variation rather than any pathology.

- Tut's Cleft Palette and Overbite: The king had a small cleft in his hard palette (the bony roof of his mouth), not associated with an external expression such as a hare-lip or other facial deformation. His lower teeth are slightly misaligned. He has large front incisors and the overbite characteristic of other kings of his family (the Tuthmosid line).

- Scoliosis or Spin Condition: There is a slight bend in the spine; however, the scientists agree that this is not a pathological scoliosis, since there is no rotation and no associated deformation of the vertebrae. This bend most likely reflects the way the mummy was positioned by the embalmers.

- Embalmers' Brain Extraction: The nasal septa were destroyed by the embalmers, and the brain was extracted through the nose.

- Embalming of Tut's Head: Principal Route. All the scientist agree, based on the differing densities of the materials and the way in which the embalming liquids (now completely solidified) appear, that various types of these liquids were introduced to the cranial cavity several times through the nose.

- At first, the body was lying on its back, and the embalming liquid pooled along the back of the skull; later, the head was tipped back in some way, and the embalming liquid pooled in the top of the skull.

- Possible Second Route for Embalming of His Head: Part of the team believed that there was evidence for a second route through which embalming liquid was introduced to the lower cranial cavity and neck.

- This would have been through the back of the upper neck. In this area, there are two layers of solidified material of a different density from that which was seen in the area above.

- The "Murder" Theory of King Tut: The entire team agreed that there is NO evidence for murder present in the skull of Tutankhamun. There is NO area on the back of the skull that indicates a partially healed blow. There are two bone fragments loose in the skull. These cannot possibly have been from an injury from before death, as they would have become stuck in the embalming material. The scientific team has matched these pieces to the fractured cervical vertebra and foramen magnum, and they believed these were broken either during the embalming process or by Carter's team.

- Tut's Missing Ribs and Sternum: The sternum and a large percentage of the front ribs are now missing, evidently along with the much of the front chest wall. The ends of the missing ribs are cleanly cut, clearly by a sharp instrument. The scientific team agreed that this cannot mirror in any way extensive trauma to the chest, as such trauma would have been reflected elsewhere in the body (particularly in the vertebra).

- Embalming Process: The team concluded, based on the identification of at least five different types of embalming material and the many episodes of its introduction to the body and cranial cavity, that great care was taken in the mummification of this king. This contradicts previous arguments that the body of the king was prepared hurriedly and carelessly.

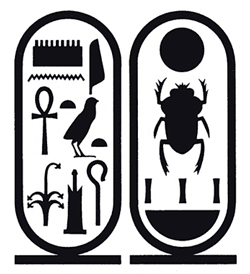

The ancient Egyptians adopted the scarab as a symbol of the sun god because they were familiar with the sight of the beetle rolling a ball of dung on the ground, and this action suggested the invisible power that rolled the sun daily across the sky.

The scarab on this pectoral, which was worn on the chest as a decoration or ornament, was made of gold openwork encrusted with lapis lazuli which was inlaid with semiprecious stones that form a picture puzzle of King Tut's ruling name, Nebkheprure.

This is just one of the many valuable items that the archeologists were looking for in and around King Tut's body and which is believed by some to have caused some of the damage to his body as shown by the CT Scans.

The first cervical (topmost) vertebra and the foramen magnum (large opening at the base of the skull) are fractured here, which according to this theory may have happened when the hole was made to pour in the embalming liquid or may have been done by Carter's team when removing the head from the mask. Part of the team disagrees, and sees no evidence for an embalming route through the back of the neck.

They believed, instead, that the embalming liquid in this area was also introduced through the nose or trickled down from the cranial cavity, and that the vertebra and foramen magnum were definitely damaged by Carter's team in the process of removing the head from mask, and could not have been damaged by the embalmers.

Fractured Leg? The team noted a fracture of the left lower femur (thighbone), at the level of the epiphyseal plate. This fracture appeared to be different from the many breaks caused by Carter's team: it has ragged rather than sharp edges, and there are two layers of embalming material present inside

Part of the team believed that the embalming material indicated that this can only have occurred during life or during the embalming process, and cannot have been caused by Carter's team. They noted that this type of fracture, unlike most of the others, is possible in young men in their late teens, and argued that it is most likely that this happened during life.

There is no obvious evidence of healing (although there may have been some which was masked by the embalming material). Since the associated skin wound would still have been open, this fracture would have had to occur a short time, days at the most, before death. Carter's team had noted that the patella (knee cap) on this leg was loose (now it is completely separated, and has in fact, been wrapped with the left hand), possibly suggesting further damage to this area of the body.

The part of the team that subscribed to this theory also noted a fracture of the right patella and right lower leg. Based on this evidence, they suggest that the king may have suffered an accident in which he broke his leg badly, leaving an open wound. Although the break itself would not have been life-threatening, infection might have set in.

Opinion among team members is divided as to whether the ribs and sternum were removed by the embalmers or by Carter's team. Carter's team does not mention that the ribs and sternum were missing, and a beaded collar and string of beads can be seen covering the chest cavity in photos taken at the time, but before their examination of the body was completed.

It is perhaps more likely that this area of the body, which is now completely missing, was removed by Carter's team in order to collect the artifacts present (although he does not mention doing so).

This cartouche, or oval figure which is shown with the front and back sides, contains the hieroglyphic signs that render Tutankhamun's personal name with his usual epithet, "Tutankhamun, Ruler of All of Upper Egypt [a name for Thebes]," and his throne name, "Nebkheperura".